http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204621904577014363024341028.html

NOVEMBER 3, 2011

Feds Shift Tracking Defense

Prosecutors in Arizona Case Drop Position That 'Stingray' Use Didn't Require Warrant

By JENNIFER VALENTINO-DEVRIES

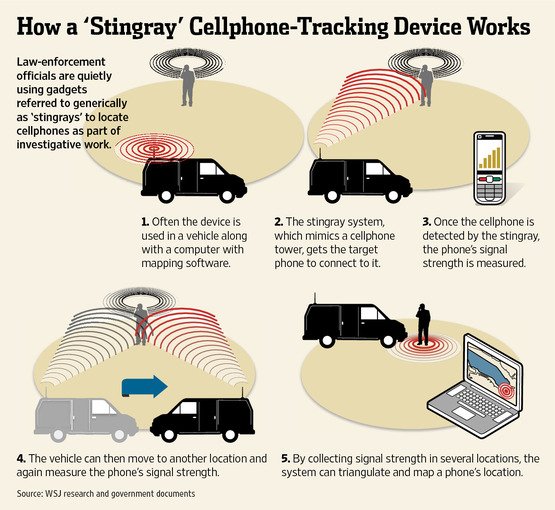

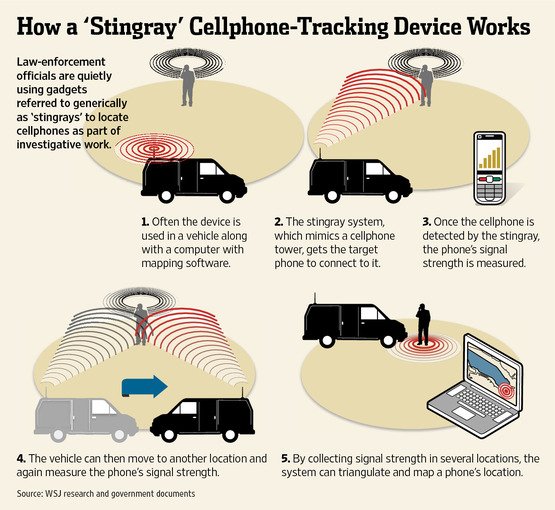

The U.S. Department of Justice now says its use of a cellphone-tracking device in a controversial Arizona case could be considered a "search" under the Fourth Amendment, a tactical move legal experts say is designed to protect the secrecy of the gadgets known as "stingrays."

For more than a year, federal prosecutors have argued in U.S. District Court that the use of the stingray device--which can locate a mobile phone even when it's not being used to make a call--wasn't a search, in part because the user had no reasonable expectation of privacy while using Verizon Wireless cellphone service. Under that argument, authorities wouldn't need to obtain a search warrant before using one of the devices.

The defendant in the case, Daniel David Rigmaiden, is facing fraud charges. His quest to force the government to provide information about the device used to locate him was the subject of front-page article in The Wall Street Journal in September.

Legal experts say the government's move fits into its strategy of keeping information about the devices under wraps, and the government continues to maintain that, in general, search warrants aren't required.

The government said it is willing to make these concessions in this case alone in an attempt to "avoid unnecessary disclosure" of information about its stingray devices. The judge in the case, David G. Campbell, had indicated he might want to know more about the technical details of the devices before ruling on whether their use constituted a search.

The government's move comes amid renewed questions about how the use of new technologies by law enforcement is challenging interpretations of the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures.

The Supreme Court is set to hear oral arguments next week in a case in which federal agents used a GPS device to track a suspect's car for a month without a search warrant. The government argues that people driving on public roads don't have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their public movements.

In the Arizona case, Mr. Rigmaiden was found after federal agents used a stingray to track a mobile device to an apartment building. He has argued that using stingrays to locate devices in homes without a valid warrant "disregards the United States Constitution" and is illegal.

In a memo filed with the court last week, the prosecution said it will agree that in this case, the "tracking operation was a Fourth Amendment search and seizure." It also will agree with some of the defendant's other assertions, including that the stingray caused a "disruption of service."

But the government's concessions don't represent a shift in policy. In the same memo, the government says its "position continues to be that, as a factual matter, the operation did not involve a search or seizure under the Fourth Amendment."

The latest filing means that in the Arizona case the government could stake its case on the argument that it did have a valid search warrant.

The defense has asserted the order wasn't, in fact, a proper search warrant, in part because it allowed investigators to delete all the tracking data collected, rather than reporting back to the judge.

The defense didn't immediately respond to a request for comment. The U.S. Attorney's Office declined to comment beyond what was in the memorandum.

In September, a Federal Bureau of Investigation representative told the Journal the policy of deletion "is intended to protect law enforcement capabilities so that subjects of law enforcement investigations do not learn how to evade or defeat lawfully authorized investigative activity."

Along with its memorandum, the government submitted an affidavit from an FBI special agent expanding on the agency's reasons for deleting data associated with stingray devices.

In the latest memo, the FBI says all data from stingrays are deleted because the devices may tend to pick up information on innocent people in addition to suspects. To ensure "that the privacy rights of those innocent third parties are maintained" after their data has been captured, all the information is deleted, including that pertaining to the subject. The defense indicated that it plans to file a response to the memorandum this week.