JANUARY 4, 2012

Data Analytics: So, What's Your Algorithm?

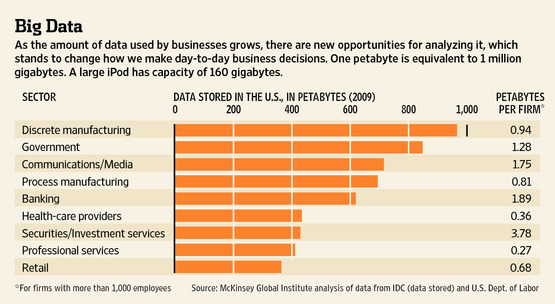

By DENNIS K. BERMAN We are ruined by our own biases. When making decisions, we see what we want, ignore probabilities, and minimize risks that uproot our hopes. What's worse, "we are often confident even when we are wrong," writes Daniel Kahneman, in his masterful new book on psychology and economics called "Thinking, Fast and Slow." An objective observer, he writes, "is more likely to detect our errors than we are." The new year will bring plenty of splashy stories about iPads and IPOs. There is a more important theme gathering around us: How analytics harvested from massive databases will begin to inform our day-to-day business decisions. Call it Big Data, analytics, or decision science. Over time, this will change your world more than the iPad 3. Computer systems are now becoming powerful enough, and subtle enough, to help us reduce human biases from our decision-making. And this is a key: They can do it in real-time. Inevitably, that "objective observer" will be a kind of organic, evolving database. These systems can now chew through billions of bits of data, analyze them via self-learning algorithms, and package the insights for immediate use. Neither we nor the computers are perfect, but in tandem, we might neutralize our biased, intuitive failings when we price a car, prescribe a medicine, or deploy a sales force. This is playing "Moneyball" at life. It means fewer hunches and more facts. Think you know something about mortgage bonds? These systems are now of such scale that they can analyze the value of tens of thousands of mortgage-backed securities by picking apart the ongoing, dynamic creditworthiness of tens of millions of individual homeowners. Just such a system has already been built for Wall Street traders. Crunching millions of data points about traffic flows, an analytics system might find that on Fridays a delivery fleet should stick to the highways-- despite your devout belief in surface-road shortcuts. You probably hate the idea that human judgment can be improved or even replaced by machines, but you probably hate hurricanes and earthquakes too. The rise of machines is just as inevitable and just as indifferent to your hatred. Business people have been having such fantasies of rationalism for decades. Until the last few years, they have been stymied by the cost of storage, slower processing speeds and the flood of data itself, spread sloppily across scores of different databases inside one company. These problems are now being solved. "We've just got to the point where the technology really starts to work," says Michael Lynch, chief executive of Autonomy Corp. Hewlett-Packard Co. just spent $11 billion to buy Autonomy, which vacuums up "unstructured data" then applies it to these analytic approaches. Of course, the hype is growing fast, too. Company valuations in this space have pushed higher, and surely some will falter along the way. That won't matter much in the long run. The story of 2012 is how these technologies are inching closer to each one of us. For a glimpse, look inside The Schwan Food Co., whose 6,000 roving sales people deliver frozen products to homes of three million customers across the country. Schwan home sales were listless for four straight years, beset by high customer churn and inventory pileups. Over 10 months, the venerable Minnesota company began a program with the aid of Opera Solutions Inc. of New York, an eight-year-old analytics firm.

Schwan already had a crude recommendation program. Its sales people could look at six weeks of orders, and suggest purchases from that list. The new project took it into more sophisticated territory: Matching seemingly disparate customers with similar purchase patterns in their past. Opera calls them finding "genetic twins." It also added ways to track whether customers' spending was fading from certain categories--say, breakfast foods--and offered product suggestions and discounts to keep the spending intact. Schwan's database is now pushing out more than 1.2 million dynamically-generated customer recommendations every day, sent directly to drivers' handheld devices. Opera says Schwan's revenues are up 3% to 4% because of it. "There is a whole class of things that couldn't be done five years ago," says Opera CEO Arnab Gupta, who just landed an $84 million venture investment from investors including Accel-KKR and Silver Lake Sumeru. His company is now valued at around $500 million. "A few years ago it might take a month to run a project involving 30 billion separate calculations. Today it can be done in two to three hours." The big goal is to push all the heavy back-end work forward to front-line workers, often as a "dashboard" on a handheld device. Soon, a drug saleswoman will have real-time analytics that tell her to focus on the doctors who spent time on social networks that morning, and who are thus more apt to influence colleagues, says Dhiraj C. Rajaram, founder of analytics company Mu Sigma, of Northbrook, Ill. Last week Mu Sigma raised $108 million in venture funding from General Atlantic and Sequoia Capital. A warning awaits, of course. As Mr. Rajaram explains, analytics will eventually become the norm, which will push adaptation and business cycles even faster than they are today. "As computers become better and better, our lives are becoming more and more complex. They create new problems as much as they solve old ones." Until then, we should take some comfort--however difficult it may feel--that machines will help us eliminate our worst human tendencies. Mr. Kahneman reminds us best: "We often fail to allow for the possibility that evidence that should be critical to our judgment is missing. What we see is all there is." The Game is a regular column covering the future of business. Follow on Twitter @dkberman or write to dennis.berman@wsj.com.