MAY 16, 2011

U.S. Balks at Pakistani Bills

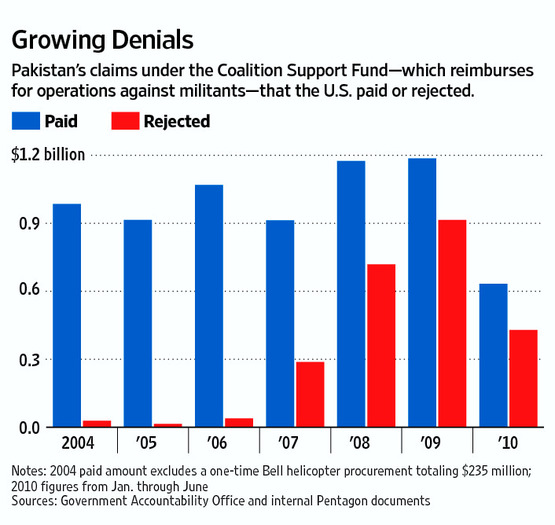

Allies Clash on Payments for Terror War; 40% of Claims Rejected

By ADAM ENTOUS

The U.S. and Pakistan are engaged in a billing dispute of sizable proportions, sparring behind closed doors over billions of dollars Washington pays Islamabad to fight al Qaeda and other militants along the Afghanistan border.

Washington, increasingly dubious of what it sees as Islamabad's mixed record against militants, has been quietly rejecting more than 40% of the claims submitted by Pakistan as compensation for military gear, food, water, troop housing and other expenses, according to internal Pentagon documents. Those records, reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, detail $3.2 billion in expense claims submitted to the U.S. for operations from January 2009 through June 2010.

According to the documents and interviews with officials, Pakistan has routinely submitted requests that were unsubstantiated, or were deemed by the U.S. to be exaggerated or of little or no use in the war on terror--underscoring what officials and experts see as a deep undercurrent of mistrust between the supposed allies.

For example, the Pakistani army billed the U.S. $50 million for "hygiene & chemical" expenses, of which the U.S. agreed to pay only $8 million, according to records covering January 2009 through June 2010. Pakistan's Joint Staff--the country's top military brass--requested $580,000 in 2009 to cover food, medical services, vehicle repair and other expenses, but the U.S. paid nothing.

In one case in the past year, the U.S. paid millions to refurbish four helicopters to help Pakistan's army transport troops into battle against Taliban and other militants. But the Pakistanis ended up diverting three of those aircraft to peacekeeping duties in Sudan--operations for which Islamabad receives compensation from the United Nations, U.S. officials said.

"This is about how much money Pakistan can extract," said Moeed Yusuf, South Asia adviser for the United States Institute of Peace, an independent research organization funded by Congress.

The billing spat has exacerbated tensions between the countries, which reached a nadir after the U.S. raided the compound of Osama bin Laden without informing Pakistani authorities. On Monday, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman John Kerry in Islamabad said the U.S. wants to hit "the reset button" to warm relations between the countries.

Pakistani officials deny they are trying to bilk the U.S. and say the increased American scrutiny has sent the message to the Pakistanis that Washington considers the army to be full of cheats. A senior Pakistani official called this "detrimental to bilateral trust." The official says Islamabad understands the need for some scrutiny but said the U.S. has gone too far: "People have to give a receipt for every cup of tea they drink or every kilometer they drive."

U.S. officials say the relationship with Pakistan remains deeply important and they praise the army for sending more than 145,000 troops to the tribal areas for operations that resulted in heavy casualties.

Nevertheless, U.S. officials say Pakistani claims have been rejected for a number of reasons, including failure to confirm that expenses were incurred in support of U.S. operations in Afghanistan and the war on terror. Some U.S. officials also fear that some of the aid is being diverted to the border with Pakistan's traditional rival, India.

Secret diplomatic cables obtained by WikiLeaks and reviewed by The Wall Street Journal show that U.S. officials were taken aback by Pakistani claims as early as 2006, including a $26 million charge for barbed wire and pickets, and for almost $70 million in radar maintenance "although there is no enemy air threat related to the war on terror."

Internal Pentagon records show U.S. rejection rates for Pakistani expense claims skyrocketed beginning in 2007 and 2008. Of the more than $3.2 billion in Pakistani claims from January 2009 through June 2010, the most recently completed reporting period, the U.S. has refused to pay $1.3 billion. Claims in 2008 were largely processed under the Obama administration, which took office in January 2009, congressional investigators say.

Denial rates have climbed from a low of 1.6% in 2005, to 38% in 2008 and 44% in 2009, the documents show. Claims are generally processed six months to a year after submission.

The discovery that bin Laden lived securely in Pakistan for so many years has led some lawmakers to demand that U.S. aid to Islamabad be curtailed.

"There is an increasing belief that [Pakistanis] walk both sides of the road," Senate Intelligence Committee Chair Dianne Feinstein, a California Democrat, told The Wall Street Journal. She called for a total U.S. aid freeze until a "credible" investigation clears Pakistan of any official complicity in harboring bin Laden.

President George W. Bush created the Coalition Support Fund soon after Sept. 11, when it became apparent that the U.S. would only be able to defeat al Qaeda and its Taliban allies in Afghanistan with help on the Pakistani side of the border. Since then, the U.S. has provided nearly $20 billion in assistance to Pakistan, including $8.87 billion to reimburse Islamabad for expenses said to be incurred fighting militants.

Coalition Support Funds are deposited directly into Pakistan's Treasury, and the U.S. has limited ability to track the money after it is transferred, U.S. official say. "This is a big problem and I think we have to find out exactly how the money has been used," Mrs. Feinstein said.

White House and Pentagon officials declined to comment on the rising rejection rates. The U.S. discloses how much it pays to Pakistan but withholds details about rejected claims to avoid exacerbating tensions. A senior Obama administration official, who also worked under Mr. Bush, said alarm bells about the payments sounded after a critical 2008 report by the Government Accountability Office sparked "painful" discussions within the Pentagon about whether Pakistani claims were receiving sufficient scrutiny.

Secret State Department cables suggest the U.S. saw the payments as inducement to get the cash-strapped Islamabad government to send troops into areas its army had long been reluctant to enter. But recent reports to Congress by the White House show frustration with what the U.S. sees as Islamabad's unwillingness to directly confront Washington's main enemies in the tribal areas--the Afghan Taliban, the Haqqani network and al Qaeda.

According to State Department cables between May 2006 and April 2009, U.S. ambassadors in Islamabad, Ryan Crocker and Anne Patterson, and top military advisers at the embassy urged Washington to overhaul the program. They wanted to require that future payments be based on Pakistan's military "performance," "behavior" and "measurable combat operations" rather than on the "mere presence" of Pakistani troops in the tribal areas.

U.S. officials declined to comment on what happened to those recommendations. But they say the claims process has been revised--particularly since the GAO report--so that submissions are reviewed multiple times by U.S. military staff, who try to link the expenditures to specific military operations.

Pentagon documents show that from January 2009 through June 2010 Pakistan tried to bill the U.S. more than $115 million for helicopter operations alone. But the U.S. has only agreed to reimburse Islamabad for about half of that amount.

Getting Pakistan's aging helicopter fleet into the fight against militants has been a top U.S. priority since at least 2009, when Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the head of the Pakistani military, warned then-Ambassador Patterson in a private meeting that he had only five Mi-17s currently operational in tribal areas.

After a May 2009 cable to headquarters titled "KAYANI IS 'DESPERATE' FOR HELICOPTERS," the State Department directed diplomatic missions in global capitals to hunt down choppers that could be shipped to Pakistan.

A few weeks later, the U.S. delivered four Mi-17s to the Pakistan army.

The U.S. refurbished another four helicopters under a special funding program and delivered them in July 2010. Those aircraft initially served in Pakistan's tribal areas. But the army soon dispatched three of them to Sudan, according to Lt. Col. Elizabeth Robbins, a Pentagon spokeswoman.

Rep. Howard Berman, the ranking Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said in a letter to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that the diversion of the helicopters was a "blatant violation" of the terms under which the U.S. agreed to pay for the upgrades. Congressional aides also said that future requests from Pakistan for military equipment will be a hard sell.

Lt. Col. Robbins said the Pentagon is now reviewing whether the deployment of the helicopters to Sudan was "in keeping with Pakistan's legal obligations."

Pakistani officials say the U.S. can't dictate how they use their own military equipment and say Islamabad participates in U.N. peacekeeping missions in Sudan and elsewhere at the urging of the U.S.

"Getting a helicopter, which is property of the Pakistani government, repaired with the able assistance of our U.S. friends, doesn't mean we rescind our right to redeploy it," the senior Pakistani official said.

--Julian E. Barnes contributed to this article.

Write to Adam Entous at adam.entous@wsj.com