December 7, 2012

They Know What You're Shopping For

'You're looking at the premium package, right?' Companies today are increasingly tying people's real-life identities to their online browsing habits.

By JENNIFER VALENTINO-DEVRIES and JEREMY SINGER-VINE

Georgia resident Andy Morar is in the market for a BMW. So recently he sent a note to a showroom near Atlanta, using a form on the dealer's website to provide his name and contact information.

His note went to the dealership--but it also went, without his knowledge, to a company that tracks car shoppers online. In a flash, an analysis of the auto websites Mr. Morar had anonymously visited could be paired with his real name and studied by his local car dealer.

When told that a salesman on the showroom floor could, in effect, peer into his computer activities at home, Mr. Morar said: "The less they know, the better."

The widening ability to associate people's real-life identities with their browsing habits marks a privacy milestone, further blurring the already unclear border between our public and private lives. In pursuit of ever more precise and valuable information about potential customers, tracking companies are redefining what it means to be anonymous.

Consider Dataium LLC, the company that can track car shoppers like Mr. Morar. Dataium said that shoppers' Web browsing is still anonymous, even though it can be tied to their names. The reason: Dataium does not give dealers click-by-click details of people's Web surfing history but rather an analysis of their interests.

The use of real identities across the Web is going mainstream at a rapid clip. A Wall Street Journal examination of nearly 1,000 top websites found that 75% now include code from social networks, such as Facebook's "Like" or Twitter's "Tweet" buttons. Such code can match people's identities with their Web-browsing activities on an unprecedented scale and can even track a user's arrival on a page if the button is never clicked.

In separate research, the Journal examined what happens when people logged in to roughly 70 popular websites that request a login and found that more than a quarter of the time, the sites passed along a user's real name, email address or other personal details, such as username, to third-party companies. One major dating site passed along a person's self-reported sexual orientation and drug-use habits to advertising companies.

As recently as late 2010, when the Journal wrote about Rapleaf Inc., a trailblazing company that had devised a way to track people online by email address, the practice was almost unheard-of. Today, companies like Dataium are taking the techniques to a new level.

Tracking a car-shopper online gives dealers an edge because not only can they tell if the person is serious--is he really shopping for red convertibles or just fantasizing?--but they can also gain a detailed understanding of the specific vehicles and options the person likes. "So when he comes in to the dealership, I know now how to approach" him, said Dataium co-founder Jason Ezell to a car-dealer conference last year, which was videotaped and posted online.

Mr. Morar, a 38-year-old hotel owner who lives in Savannah, Ga., has been looking carefully at the 2013 BMW X5 sport-utility vehicle, checking recent sale prices for specific configurations. Dataium declined to say specifically what, if anything, it knows about him.

Dataium said dealers can see only an analysis of the person's behavior, not the raw details of every car site a person visits. The information is tied to people's email addresses only when people provide them to a dealer voluntarily, Dataium said.

The company that owns the dealership Mr. Morar visited, Asbury Automotive Group Inc., said it gives privacy notices to customers "regarding the use of nonpublic personal information." It declined to comment on whether it had used information about Mr. Morar provided by Dataium.

Companies that conduct online tracking have long argued that the information they collect is anonymous, and therefore innocuous. But the industry's definition of "anonymous" has shifted over time.

After an epic regulatory battle in the early 2000s over Web privacy, the online ad industry generally concluded that "anonymous" meant that a firm had no access to "PII," the industry term for "personally identifiable information." Now, however, some companies describe tracking or advertising as anonymous even if they have or use people's real names or email addresses.

Their argument: It's still anonymous because the identity information is removed, protected or separated from browsing history. Facebook Inc., for example, offers a service that shows ads to groups of people based on email address, but only if advertisers already have that address. Facebook says that it doesn't give people's email addresses to the advertiser.

"We will serve ads to you based on your identity," said Erin Egan, chief privacy officer at Facebook, "but that doesn't mean you're identifiable." Facebook, Rapleaf and other companies also say that they anonymize their data.

How does anonymization work? A website uses a formula to turn its users' email addresses into jumbled strings of numbers and letters. An advertiser does the same with its customer email lists. Both then send their jumbled lists to a third company that looks for matches. When two match, the website can show an ad targeted to a specific person, but no real email addresses changed hands.

Still, the sheer ease with which personal details can be shared online makes it difficult for people to know whether their information is safe. A Wall Street Journal survey of 50 popular websites, plus the Journal's own site, found that 12 sent potentially identifying information such as email addresses or full real names to third parties.

The Journal tested an additional 20 sites that deal with sensitive information, including sites dealing with personal relationships, medical information and children. Nine of these sent potentially identifying information elsewhere.

Sometimes the information was encoded and sent in a special transmission to another company. Other times, though, people's names were simply included in the title or address of the Web page. This information gets sent automatically to every ad company with a presence on a Web page unless the website owner takes steps to prevent it.

The Journal's own website shared considerable amounts of users' personal information. It sent the email addresses and real names of users to three companies. The site also transmitted other details, including gender and birth year, which WSJ.com allows people to submit when they fill out their website profile.

A Journal spokeswoman said that most of the sharing of personally identifiable information was unintentional and was being corrected. The only intentional sharing of identity information, she said, was an encoded version of the user's email address, provided to a company that sends marketing emails to readers who opt to receive them. She said the Journal makes companies it works with sign a policy that would prevent them from using improper data they receive.

Another site sharing considerable information, the free dating service OKCupid, sent usernames to one company; gender, age and ZIP Code to seven companies; sexual orientation to two companies; and drug-use information--do you use drugs "never," "sometimes" or "often"?--to six companies. It also sent an anonymized version of email addresses to a firm that says it uses them to help businesses get information about customers in their email lists.

"None of this information is personally identifiable," said OKCupid's chief executive officer, Sam Yagan. He said OKCupid, owned by IAC/InterActiveCorp, is upfront with users about the amount of data it collects. "Advertising is and always will be part of the business model. It allows the product to be free," he said.

The regulatory clash over Web privacy in the early 2000s established ground rules that today are being tested. At that time, the Federal Trade Commission investigated the merger of the online-ad company DoubleClick Inc. with a traditional mailing-list giant, Abacus Direct, over concerns that Abacus would merge its lists of people's real names and addresses with DoubleClick's Web-browsing profiles.

DoubleClick (now owned by Google Inc.) eventually agreed not to do that. The dispute spawned an industry self-regulatory group that pledged not to link personally identifiable information to Web browsing unless the person opted in.

But the allure of real identities remains. After all, that's how most companies keep track of their customers. Brick-and-mortar shops can "capture things like name, city and email address" when a person buys something or signs up for a loyalty card, said a Yahoo Inc. official.

Yahoo offers a service, Audience Match, that lets retailers find and target their customers online. Yahoo says that it uses anonymization and doesn't give names or Web-browsing information to advertisers.

In the past, tracking companies and retailers had a tougher time identifying online users. Today, a single Web page can contain computer code from dozens of different ad companies or tracking firms. These separate chunks of code often share information with each other. For example: If, like Mr. Morar the car-shopper, you give your name to a website, it can sometimes be seen by other companies with ads or special coding on the site.

It's so easy to share such information that many of the sites the Journal contacted said they were doing so accidentally. The problem is easy to solve, but it has persisted for years.

Craig Wills, a computer-science professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, published research in 2011 showing that 56% of more than 100 websites leaked pieces of private information in ways similar to those found in the Journal's study. "Information goes in, but we don't know if it's being dropped and ignored or saved for later use," he said.

The rise of social networks is also making it easier to tie people's real identities to their online behavior. The "Like" button, for instance, can send information back to Facebook whenever Facebook users visit pages that have the button, even if they don't click it.

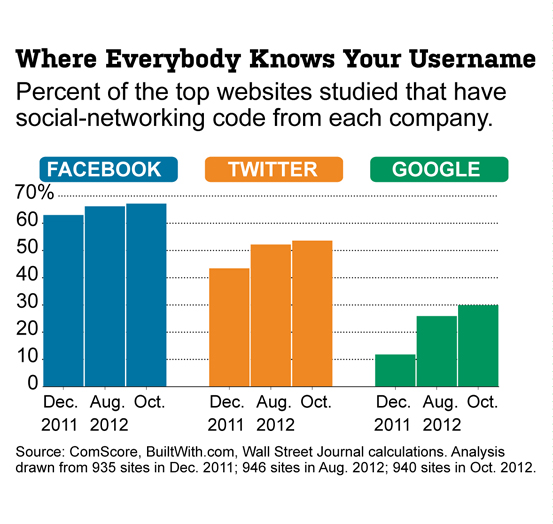

These buttons and related code give social networks, which often know people's real names, an unprecedented overview of online behavior. The Journal found that Facebook code appears on 67% of the more than 900 sites of the top 1,000 that were scanned by BuiltWith.com, a service that examines websites and the technologies they use. That is up from about 63% a year or so ago. Code from Twitter Inc. was on nearly 54% of sites, up from 43%. Code from the Google+ social network was on almost 30% of sites examined, up from just 12% in December 2011.

Google said it keeps its social-networking data separate from its ad-tracking network and doesn't use the data from unclicked Google+ buttons. Twitter says it analyzes the data from its unclicked buttons to recommend other people a user might want to follow, but not for other purposes. Facebook says it uses data from unclicked "Like" buttons only for security purposes and to fix bugs in its software.

Facebook has been expanding its ad services that use identification data. This year, the company began telling advertisers how much sales in stores increased as a result of ads on Facebook--even if the products were purchased offline. To achieve this, Facebook says it works with a company, Datalogix, that controls a vast database culled from people's use of loyalty-card programs.

Dataium, the company that watches car shoppers, is also able to tie online shopping data to people's names, according to its public statements. Based in Nashville, Tenn., Dataium was founded in 2009 by Mr. Ezell, who had previously founded a company that created websites for auto dealers, and by Eric Brown, who had experience in marketing.

The two realized that the auto industry "is trying to sell the consumer a car they want the consumer to buy, not a car the consumer wants to buy," Mr. Brown, the company's chief executive, said in an email.

Mr. Brown said that the vast majority of Dataium's business involves providing general data about online car-shopping trends. But the company also enables dealers to see information about people in their customer database--in other words, people who have given the dealer their names and email addresses.

On its website, Dataium says it observes more than 20 million shoppers across 10,000 car websites, although it doesn't claim to have identification information on everyone. Mr. Brown said personally identifiable information is "less than 1%" of total data sent to Dataium.

Dataium knows "all the websites [a] person has visited in the shopping process" and "all the vehicles this person has looked at," Mr. Ezell said at last year's car-dealer conference. So if someone looked only at Nissans, the salesman will know he needn't discuss other cars, "because I know he's a loyal Nissan shopper." For users who are identifiable, Dataium is able to add analysis based on these observations to their name.

Asbury Automotive Group, which owns 77 dealerships including Nalley BMW, the site Mr. Morar visited, announced last year that it was using Dataium's code "to obtain a greater understanding of how auto shoppers are engaging" with its stores.

Mr. Morar, the Savannah car-shopper, is still in the market for a BMW sport-utility vehicle. He has twin 8-year-olds, and they need some elbow room, he says.

But scoring the best price will be important to him, which is why he has been doing lots of research online. "I'm just trying to get as much information as I can so when I do go to the dealer I'm prepared," he said. "There's that mentality that all car dealers are out to get you."

--Ashkan Soltani contributed to this article.

Write to Jennifer Valentino-DeVries at Jennifer.Valentino-DeVries@wsj.com

What They Know: Digital Privacy