http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303879604577410481496895786.html

May 17, 2012

U.S. Rethinks Secrecy on Drone Program

By JULIAN E. BARNES

WASHINGTON--The Obama administration is weighing policy changes that would lift a tattered veil of secrecy from its controversial campaign of drone strikes, a recognition that the expanding program has become a regular part of U.S. global counterterrorism operations.

U.S. drone strikes are hardly a secret. Officials have spoken openly about them, even discussing the operations in formal speeches. But they are still classified, and unauthorized disclosures about details of individual missions could constitute a felony.

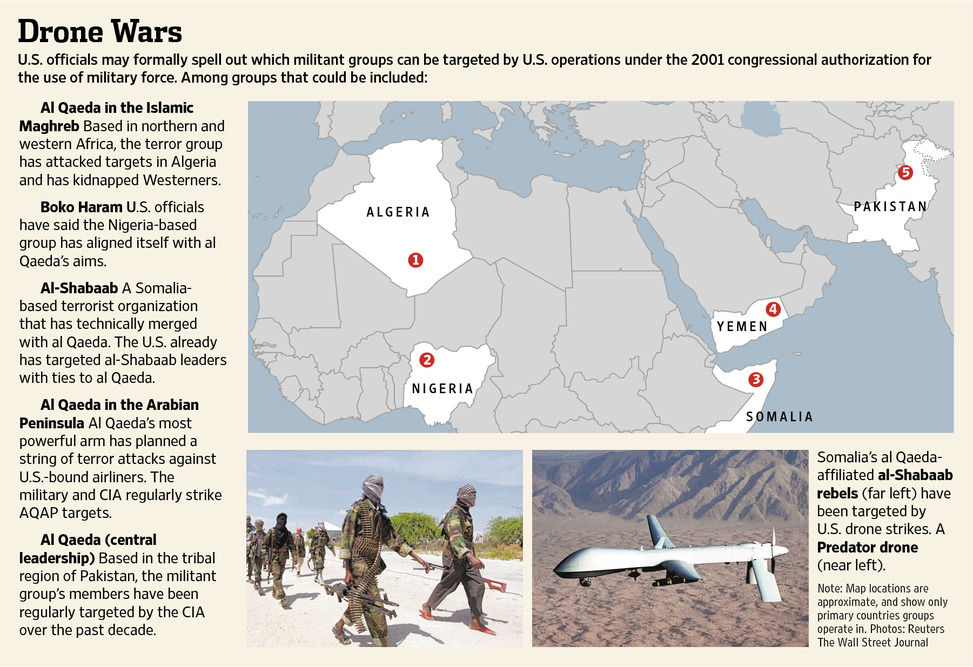

The policy changes under consideration could include specifying which extremist groups associated with al Qaeda can be targeted by the Pentagon under the 2001 congressional authorization for the use of military force against perpetrators of the Sept. 11 attacks, according to U.S. officials.

The debate has been given urgency by lawsuits seeking information on drone strikes; the government must formally respond with motions stating its position and why it will deny the requests, or fill them.

But many officials also believe that it is time to re-evaluate U.S. policies on secrecy about the targeted-killing program, saying that greater openness could defuse criticism of the practice.

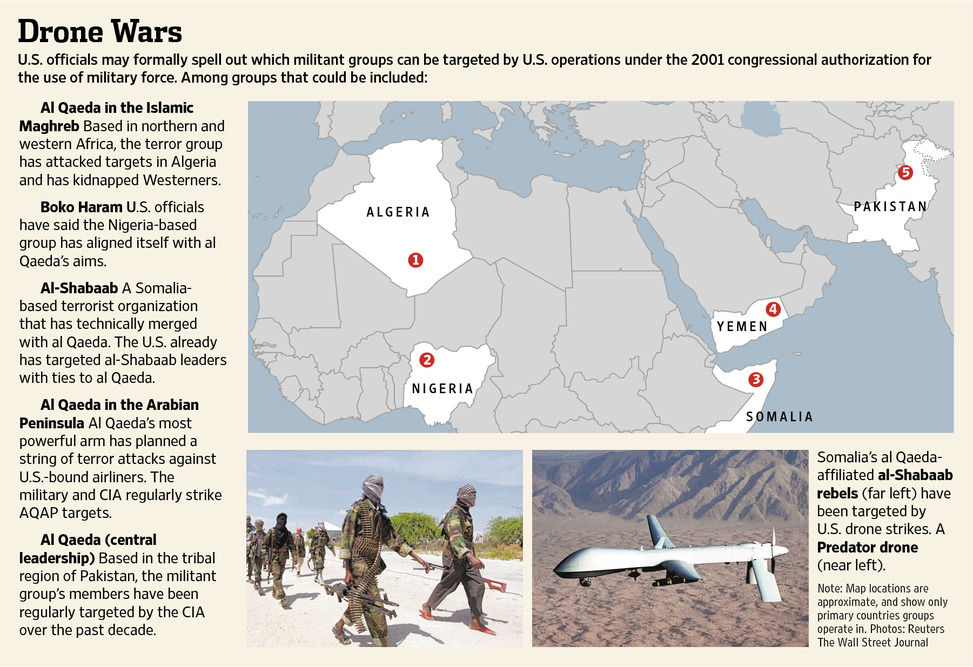

Unmanned aerial strikes on terrorist suspects began after the Sept. 11 attacks, at first as a rare occurrence. Under the Obama administration, drone strikes by the Central Intelligence Agency and the military have become increasingly common as a primary tool in U.S. national-security strategy.

The Pentagon has a policy of disclosing traditional military operations once they are complete. But rules for counterterrorism strikes haven't kept up with their expanded use. Pentagon officials still routinely decline to discuss details of operations in Yemen or Somalia at news conferences as a matter of policy, while more freely discussing counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan.

The changes considered most likely to win adoption would bring about greater openness regarding the military drone program, while keeping most or all details of CIA strikes classified, U.S. officials said. CIA officials are opposed to publicly acknowledging the details of drone programs under its control, for fear of setting precedents that could affect other covert programs.

Two lawsuits by the American Civil Liberties Union, in March 2010 and February 2011, sought CIA records on its program of targeted killing with drones. Separately, the New York Times sued for access to the administration's legal justifications for the 2011 CIA drone strike that killed Anwar al-Awlaki, a U.S. citizen and top leader of al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

The Obama administration is due to answer the lawsuits in New York and Washington on Monday, after winning a series of extensions. In an extension request in April, the Justice Department said the government's response "is being deliberated at the highest level of the executive branch."

Some U.S. officials believe they will prevail in the courts if they choose to keep the drone program secret and refuse to provide any documents sought in the lawsuits.

But others think the government should voluntarily provide at least some information in response to the case. In the administration debate, some of those who advocate greater openness say it would help counter accusations that civilians are routinely killed.

Others, with one eye on the history books, believe it is important to show that strikes are carried out within the law. "If stories could be told, Americans and others would be persuaded these strikes are done in a careful way," a U.S. official said.

Instead, information about strikes is inconsistent. Government officials speaking privately in many cases release more information about covert CIA drone strikes in Pakistan than defense officials are allowed to discuss about military drone strikes in Yemen.

Administration officials considered revealing more about U.S. military operations in Yemen and Somalia as part of a speech last month by John Brennan, the top White House counterterrorism adviser. The speech formally acknowledged that the U.S. uses drones to target terrorists, but officials couldn't agree on how much more to say, administration officials said.

Since that speech, Pentagon public-affairs officials have continued to refuse to provide any details of strikes in Yemen.

Complicating the debate, the military and CIA conduct similar counterterrorism strikes against al Qaeda's Yemen affiliate. Intelligence officials worry that if the Pentagon begins describing their operations more fully, details of the CIA's concurrent strikes could be revealed.

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta already has publicly has acknowledged U.S. operations in Yemen. Mr. Panetta said recently that the military has been "very successful at going after the leadership" of al Qaeda in Yemen.

Some officials are also pressing the U.S. to more fully describe the terrorist groups the U.S. is at war with under Congress's 2001 authorization for the use of military force, also called the AUMF.

While Mr. Brennan in his speech last month offered a list of al Qaeda affiliates that pose a danger, U.S. officials have never publicly listed which terrorist groups are considered associated forces of al Qaeda that can be targeted by the military.

Some legal scholars have asked for a fuller accounting of what terrorist groups the administration believes can be targeted under the congressional authorization. Robert Chesney, a professor at the University of Texas Law School, said it would be helpful for the administration to clarify which groups or individuals can be targeted under its definition of the congressional authorization.

"At the end of the day, the core concern some have with the 'associated forces' idea is that they don't know where it stops," said Prof. Chesney. "Explaining what the necessary or sufficient conditions for identifying such groups would do much to show that the government recognizes meaningful limits to its authority under the AUMF."

--Siobhan Gorman and Evan Perez contributed to this article.

Write to Julian E. Barnes at julian.barnes@wsj.com