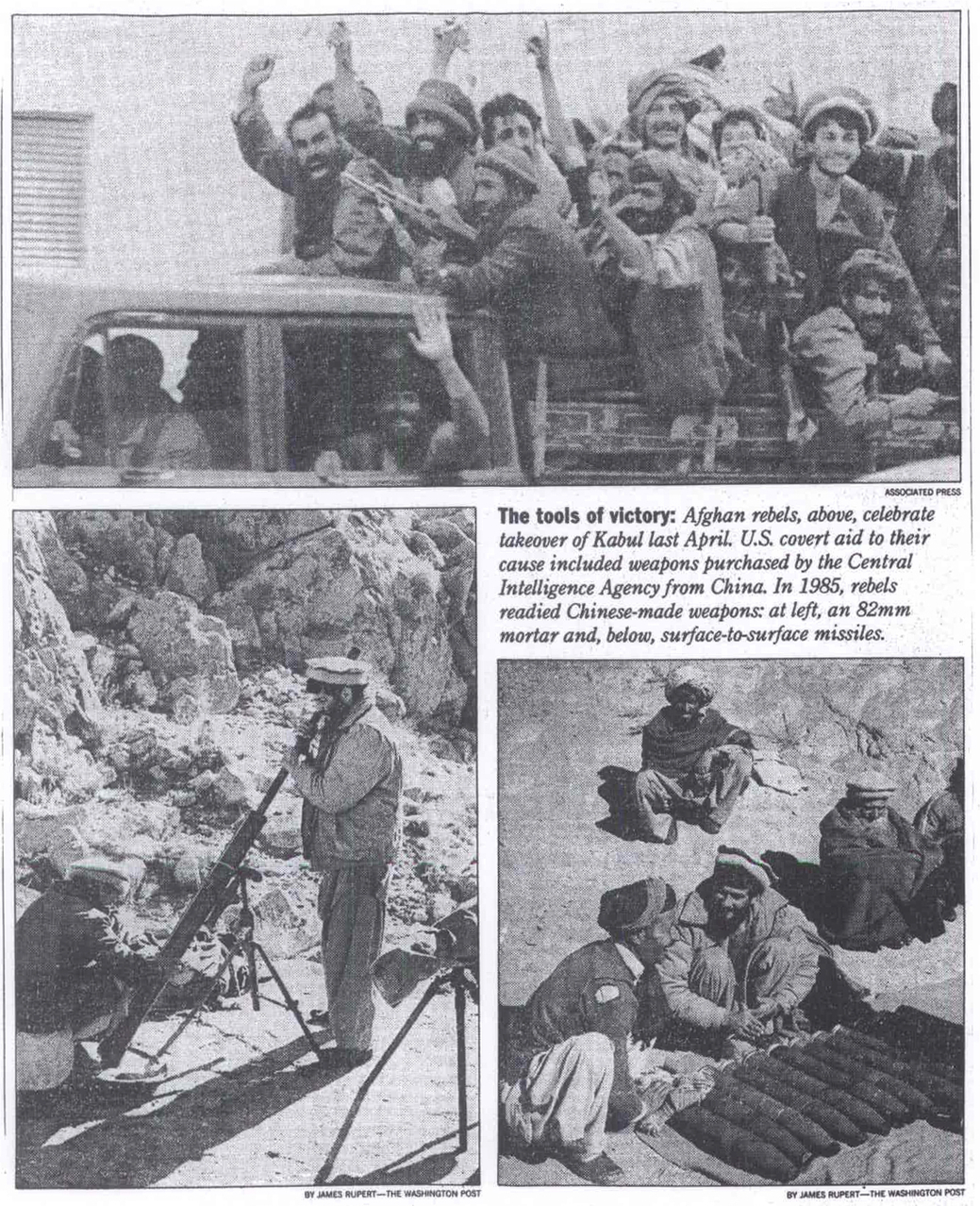

http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/Weisberg Subject Index Files/C Disk/CIA Afghanistan/Item 03.pdf In CIA's Covert Afghan War, Where to Draw the Line Was Key July 20, 1992 Last of two articles By Steve Coll, Washington Post Foreign Service As part of the CIA's annual "shopping list" exercise in which Pakistan's intelligence service ordered guns and ammunition from the agency for use by Afghan mujaheddin rebels, the CIA station chief in Islamabad in 1985 transmitted to his superiors an unusual request: The Pakistanis wanted "packages" of long-range sniper rifles and sophisticated sighting scopes. When the request circulated among members of the Reagan administration team that was supervising the covert Afghan program, U.S. intelligence officials said the Pakistanis intended to supply the sniper rifles to Afghan rebels so they could infiltrate Afghanistan's capital of Kabul and kill senior Soviet generals stationed there, Western sources said. If Washington chose to assist the plan, there was reason to believe it might succeed. In response to National Security Decision Directive 166, signed by President Reagan in March 1985, the Reagan administration had sharply escalated its covert operations in Afghanistan, in part by stepping up satellite reconnaissance and other intelligence collection on the Afghan battlefield. The U.S. intelligence pinpointed the residences of leading Soviet generals in Kabul and regularly tracked their movements, as well as those of visiting commanders from Moscow and Tashkent, officials said. The sniper-rifle request posed a delicate issue for the Reagan administration: How far was it prepared to go in trying to defeat the Soviet Union in Afghanistan? Pressed by conservative activists, the administration had decided to expand its earlier policy of covert "harassment" of Soviet occupiers in Afghanistan by directly challenging the Soviet military command--a change they hoped would win the war. At a time of high tension in U.S.Soviet relations, the United States had opened its high-tech military and intelligence arsenal to help the mujaheddin confront Soviet forces in Afghanistan. Yet the question of which tools might be seen as too provocative--by either the Soviets or U.S. critics--was continually a sensitive one. Among other things. those involved had lawyers looking over their shoulders. CIA and administration attorneys feared that targeting the Soviet military command might land CIA officers or administration officials in jail because killing Soviet generals could be seen as violating the 1977 presidential directive against CIA involvement in assassinations, U.S. officials said. If the CIA station chief provided the rifles "with the intent" to kill specific Soviet generals then "he will go to jail," an official said administration lawyers argued during this legal debate. The question then arose, "How about if he does it without knowing what they're going to be used for?' But CIA lawyers responded that it was "too late" because the plan to kill specific Soviet generals had been consigned to writing in CIA cables between Washington and Pakistan. To some involved in the debate, such as Vincent Cannistraro, a CIA operations officer then posted as an intelligence official on the National Security Council staff, shooting Soviet generals in Kabul did not seem much different from encouraging mujaheddin rebels to kill Soviet officers in helicopters with antiaircraft missiles. Assassination "is really not a relevant question in a wartime scenario," Cannistraro said in an interview. One problem was the presidential "finding" or classified legal authorization for the U.S. covert program in Afghanistan, which dated to the Carter administration and described the purpose of U.S. aid as the "harassment" of Soviet forces. Although the Carter finding had been augmented by Reagan's National Security Decision Directive 166, the language in the original finding remained a key legal basis of the covert program. We came down to, is 'harassment' assassination of Soviet generals?" said an official. "The phrase 'shooting ducks in a barrel' was used," an official recalled of the discussions. Those who favored providing the sniper packages "thought there was no better way to carry out harassment than to 'off' Russian generals in series," an idea that would be "unthinkable" to the U.S. State Department and to other Reagan administration officials. Ultimately, a decision was made to provide the sniper rifles requested by the Pakistanis--but without night vision goggles or intelligence information that would permit effective assassination of Soviet generals in Kabul, officials said. Mohammed Yousaf, a Pakistani general who supervised covert aid between 1983 and 1987, recalled in an interview receiving more than 30 but less than 100 sniper rifles. With CIA assistance, Pakistan--which felt threatened by Moscow's control of neighboring Afghanistan and was eager to cooperate with the United States in opposing the Soviet occupation--held a two-day training course to teach mujaheddin rebels how to use the rifles against "military targets," including what a U.S. official said were "trucks and armored personnel carriers." Urban Sabotage A similar issue concerned urban sabotage. During the mid-1980s, the CIA aided Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) in establishing and supplying two secret mujaheddin training schools in guerrilla warfare, including one that concentrated on urban sabotage techniques, according to Yousaf. Pakistani instructors trained by the CIA taught Afghans how to build and conceal bombs with C-4 plastic explosives and what Yousaf estimated were more than 1,000 chemical and electronic delay bomb timers supplied by the CIA. The principal idea was to carry out attacks against military targets such as fuel and ammunition depots, pipelines, tunnels and bridges, Yousaf and Western sources said. Some mujaheddin trained at the CIA-assisted guerrilla schools used the materials and training supplied to carry out a number of car bomb and other assassination attacks in Kabul under ISI direction, according to Yousaf. By his account, a graduate of the urban sabotage school nearly blew up future Afghan president Najibullah in downtown Kabul in late 1985, when Najibullah was chief of the hated Afghan secret police. "We made numerous attempts to kill Najibullah," Yousaf wrote in a recently published memoir of the secret war titled "The Bear Trap." Yousaf said that dominant in his mind was the view that "Kabul is the center of gravity" in Afghanistan and that it was essential that Soviet occupiers "should not feel safe anywhere." At the same time, he said, no attacks on civilian targets were deliberately planned by Pakistan, the CIA or the mujaheddin. Western officials said they did not sanction car-bomb or similar attacks but that they could not control the use of bombs and weapons they had supplied. "The reality is that you don't know what the people are going to do with the weapons you give them, whether [delay detonators] or AK-47s or whatever," said a U.S. official. "We did as best we could to be sure the weapons and training supplied were directed to military targets, broadly defined." The CIA exercised relatively little control over specific mujaheddin attacks because the agency ceded operational responsibility to the Pakistanis. This was an enduring feature of the covert program's basic structure. The United States supplied funds, weapons and general supervision. Saudi Arabia matched U.S. financial contributions and China's government sold and donated weapons. But the dominant operational role on the front lines belonged to Pakistan's ISI, which insisted on control, For most of the war, no Americans trained mujaheddin directly--instead, the CIA trained Pakistani instructors. Particularly during the post-1985 escalation, CIA officers lobbied their Pakistani counterparts to carry out certain kinds of guerrilla operations and to permit greater U.S. involvement, Yousaf and Western sources said. But the ISI resisted such requests and decision-making rested ultimately with the Pakistanis and the Afghans. "The CIA believed they had to handle this as if they were wearing a condom," said Cannistraro, who advocated more direct involvement. Within the U.S. government, the post-1985 escalation was supervised by an interagency committee chaired by a member of Reagan's NSC staff that included representatives from the Pentagon, State Department and CIA. Early in 1987, some officials within the Reagan administration pushed for a transfer of the Afghan covert program from the CIA to the Pentagon, where Special Forces and other paramilitary specialists sought greater involvement with the mujaheddin. This proposal was rejected by national security adviser Frank Carlucci and his deputy, Gen. Colin Powell, after a vigorous debate, Western officials said. The Chinese Connection To thwart Soviet military escalation in Afghanistan during the mid-1980s, conservative supporters of the mujaheddin, particularly those in Congress, believed they faced two major challenges. They felt the Afghan rebels urgently needed an effective weapon to destroy aircraft and helicopter gunships used by Soviet special forces. And they wanted to harass and destroy strategic targets in Afghanistan dear to the Soviet military command. In January 1986, these twin goals brought Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) to China. Flanked by two senior CIA operations officers whom he suspected had been sent to "watch over me," Hatch sat with China's intelligence chief in a Beijing office. That Hatch, an ardent conservative and anti-communist, found himself cajoling one of the world's most important communist spy masters reflected the way the Afghan covert program tended to produce strange bedfellows. The meeting also highlighted China's influential role in the CIA's Afghan operations. From the beginning, China provided a key link in the covert logistics pipeline through which arms and ammunition reached the Afghan rebels based in Pakistan, according to Pakistani and U.S. sources. Frightened of soviet expansionism, the Chinese privately encouraged the United States to take on the Soviet army in Afghanistan, and Chinese intelligence officials offered extensive assistance. During the early years of the covert Afghan program, the CIA purchased the bulk of the weapons earmarked for the mujaheddin from the Beijing government and arranged for their shipping to the Pakistani port of Karachi, Yousaf and Western sources said. Later, the CIA further diversified its purchases and bought many weapons from Egypt, in part to save money, U.S. sources said. A U.S. official involved estimated that by the mid-1980s the Beijing government earned $100 million annually in weapons sales to the CIA. "The Chinese were supportive and were also making money--a considerable amount of money," he said. Yousaf said the Chinese typically donated about 10 percent to 15 percent of the weapons and ammunition sold annually to the CIA, although the CIA had to pay for shipping these materials to Karachi. To protect secrecy, the weapons typically were copies of Soviet ones, although some of those delivered had Chinese markings. Hatch traveled to Beijing because he wanted Chinese support for more than just weapons supplies. The senator was accompanied by some of the key officials who helped manage the covert Afghan program, including Morton Abramowitz, director of intelligence and research at the State Department; Cannistraro from the NSC staff; Michael Pillsbury, assistant to the defense undersecretary for policy planning; Fred Ikle, the CIA station chief in Beijing; and the deputy chief of the CIA's operations directorate. In consultation with these intelligence officials, Hatch urged the Chinese to support the escalation of U.S. covert aid now underway, particularly the new efforts to hit key targets with sophisticated guerrilla strikes. U.S. demolition experts equipped with detailed satellite intelligence were helping the Pakistanis plan operations against these targets, sometimes with Pakistani intelligence officers accompanying Afghan rebels on the raids. But Hatch wanted Chinese support as well, the senator recalled in an interview. The Chinese intelligence chief agreed, according to Hatch and other sources. Hatch then asked the Chinese official if he would agree to support the supply of U.S.-made Stinger missiles to the Afghan rebels, and if he would communicate his support directly to Pakistani President Gen. Zia ul-Haq as part of a coordinated lobbying effort. Although supplying Stingers would mark a departure from U.S. policy not to provide weapons that could be traced directly to the CIA, Hatch and others believed the missiles were needed desperately by the mujaheddin. Other antiaircraft weapons--including surface-to-air missiles sold in large quantities to the CIA by the Chinese government--had been tried and had failed. Pressed by Hatch and aware that the senator was surrounded by representatives of the entire U.S. intelligence apparatus, the Chinese intelligence chief agreed to the Stinger request, Hatch and others said. Hatch's party then flew to Pakistan and made the same pitch to Zia, who agreed for the first time to accept the Stingers. Six months later, after a lengthy internal Reagan administration fight that pitted a reluctant CIA and U.S. Army against bullish Pentagon and State intelligence officials, the Stinger supply program began. In retrospect, many senior U.S. officials involved see the decision as a turning point in the war and acknowledge that Hatch's clandestine lobbying played a significant role. The Stingers proved effective against the Soviet helicopter gunships used by the Spetsnaz special forces. Yousaf said the supply agreement called for the United States to send about 250 "grip stocks" or launchers annually, along with slightly more than 1,000 missiles. Estimates of the mujaheddin success rate in firing the heat-seeking missiles vary widely from about 30 percent to 75 percent, Western officials said, but in any case, many on the U.S. side believe the missiles helped encourage the Soviets to "abandon the doctrine they thought would win the war," as one official put it. Logistical Controversies Throughout the Afghan war, critics of the CIA's covert operations voiced two major complaints: that large amounts of weapons and money earmarked for the mujaheddin were being stolen, and that CIA reliance on Pakistani intermediaries meant too many resources were being funneled to Islamic fundamentalist elements in the Afghan resistance. Much remains unclear about these two controversial questions, but some new information has come to light. Secrecy shrouded the logistics pipeline. Purchases of weapons from China, Egypt and even communist Poland generally were made or coordinated by CIA logistics officers in Washington, Yousaf and. Western sources said. Many of the deals, particularly with China, were handled at a government-to-government level through intelligence liaisons, but others were routed through the private arms market, sources said. When a ship laden with weapons was about to arrive in Karachi, the CIA station in Islamabad informed Yousaf of the details and then Pakistani intelligence agents arranged for unloading and shipment by rail and truck to the Afghan border, Yousaf and Western sources' said. Sometimes the Chinese military attache in Pakistan was present in Karachi to monitor the process, and the Chinese generally demanded strict accounting, Yousaf said. The CIA station in Islamabad received paper receipts for ultimate deliveries to the mujaheddin. At first the receipts were provided annually,. then semiannually and later quarterly as CIA demands for more accountability increased. The Pakistanis continually complained about the quality of weapons received. Early antiaircraft systems such as the Oerlikon and Blowpipe were highly ineffective, both sides agree. Egyptian supplies of World War II-vintage weapons often arrived with empty boxes and unusable ammunition, Yousaf said. "We were in a business we had never been in before at that scale," said a U.S. official. "We were in a learning situation. There were mistakes made, [but] the quality evened out and in fact improved over the course of the war." There were incidents of obvious corruption. Yousaf recounts one from 1983 where a Karachi arms merchant bought hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition for .303 rifles from Pakistan's military ordnance factory--then controlled by Zia's martial-law regime--and sold them to the CIA. The ammunition was loaded onto a boat in Karachi, which then steamed into the Arabian Sea, turned around and returned to Karachi, at which point the CIA informed Pakistan's intelligence service that a shipment of bullets had arrived. When Pakistani logistics officers, unaware of the transaction, opened the boxes, they found the bullets all had the initials "POF"--for the Pakistan Ordnance Factory--stamped on them. To maintain secrecy, the bullets all had to be defaced at CIA expense, Yousaf said, adding that he personally handled accounting of the defacement payments from the CIA. U.S. officials said they could not recall the incident. U.S. officials contended that under pressure from Congress, they continually investigated charges of corruption and found little evidence to support them. "I'm positive there are some people who have grown rich or at least wealthier on this," said a U.S. official, but "we have no hard evidence and we did look." For his part, Yousaf said corruption in the program was minimal. Both Pakistani and Western sources agree fundamentalist parties in the Afghan resistance received the lion's share of weapons, but they dispute charges made by some in the U.S. Congress that one ambitious fundamentalist leader. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, received up to 50 percent of the guns and money. Yousaf said that when he left his job in 1987, Hekmatyar received about 18 percent to 20 percent of the annual allocation, and that all four Afghan fundamentalist parties combined received about 75 percent, leaving relatively small amounts for the three moderate parties. Hamid Gul, one of Yousafs successors at ISI, described a similar percentage for Hekmatyar. U.S. and European sources said these numbers are accurate, although they said Hekmatyar's weapons tended to be of much higher quality than his rivals', in part because his forces showed they could use the high-tech weapons and communications supplied by the CIA in large numbers beginning in 1985. A Mixed Victory? In February 1989, the last Soviet soldier left Afghanistan. At CIA headquarters in Langley, operations officers and analysts drank champagne. Today, some involved in the Afghan program say they believe the Soviet defeat was one of several decisive factors that helped discredit Soviet hard-liners and encourage Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms. And there is little doubt that defeat in Afghanistan had a profound impact on Soviet society in the late 1980s, as the Soviet empire unraveled. After the Soviet withdrawal, the covert operation in Afghanistan was marked by heightened bickering, as diplomats increasingly usurped the role of the intelligence agencies. In Washington, CIA and State Department officials battled over whether to pursue a military victory over the leftist Kabul government or make peace. That debate ended last September with a U.S.-Soviet agreement to cut off all arms to warring Afghan factions. When the deal was implemented on Jan. 1, 1992, the U.S. covert program in Afghanistan effectively ended. To some who managed the Afghan program, the violent factionalism that accompanied the mujaheddin victory in April suggested that the CIA had done too little to promote political success for the Afghans, in addition to the military victory. To many in Pakistan, U.S. abandonment of the alliance seemed final evidence of a ruthless, fickle America that never cared very much about anything other than turning back the Soviet tide in central Asia. But even Pakistani critics such as Yousaf acknowledge that without the U.S. covert program, the result in Afghanistan probably would have been much different. Although Yousaf and other Pakistani intelligence officials accuse the CIA of conspiring to undermine the Afghan holy war after Soviet troops withdrew, many also contend, in Yousaf s words, that "without the intelligence provided by the CIA many battles would have been lost, and without the CIA training of our Pakistani instructors the mujaheddin would have been fearfully ill-equipped to face, and ultimately defeat, a superpower."

Transcription by Good Times

Transcription by Good Times